I must have been about ten years old when I first realized that I was going to die someday.

I was washing the dishes after dinner, which, for a family of nine, is no small chore, and I was looking out the kitchen window and feeling trapped. The sun was already going down, which meant that the amount of time left to still get outside was dwindling. In fact, my whole summer was dwindling and darkening and had conjured up in me the usual boredoms and disappointments. This was supposed to be a joy, this summer. I was supposed to be having fun.

While I stood there rinsing a plate I thought, some day I’m going to die.

And before I could take the words back, before I could unthink them, I knew that what I’d just thought was actually true. I was going to die. And nobody could stop it from happening. It had nothing to do with me being good or bad. I was going to die. We all were.

I left the kitchen and walked into the living room. My father was reading in his permanently depressed spot on the couch, his left hand holding a cigarette, his right hand holding a book, his right elbow resting on the permanently greased arm of the couch where he lay his hair-product-shellacked head every night. My mother was folded in on herself in her red chair watching television, holding in her fist a flattened, empty pack of Vantage cigarettes that she unthinkingly agitated as she watched, making the cellophane wrapper on the pack quietly squeak like some tiny thing she was killing over and over.

I looked at them. Neither one of them looked at me.

What was I going to say? I’m going to die? If I was going to take that risk, then why not go all out and scream, “WE’RE ALL GOING TO DIE!”

But I knew my audience. And it depressed me to imagine, beyond maybe a sigh and an exhausted eye-roll from my mother, the complete lack of a response I could expect. Besides, what could they do? It was going to happen to them, too.

We were doomed.

I went back to the kitchen. I finished the dishes.

Life went on.

* * *

Because that’s the impulse, isn’t it? To go on. To believe that life goes on. Dying is the last thing you and I as human beings will ever do – but people want to believe and find great comfort in believing that life or something like it continues after dying. Death is just a speed bump, a hiccup, a glitch. You can get over it. You can keep going.

* * *

Jacques Godard’s life, as far as his own consciousness was concerned, was a meager affair; in the consciousness of others it scarcely existed at all.

Not an auspicious or flattering beginning. But as it turns out for Jacques Godard, the protagonist of Jules Romains’ 1911 novel, The Death of a Nobody, that’s fine – because two pages later he’ll be dead. And then the book can really begin.

A widower of five years and a man of humble habits, Jacques Godard is a retired train engineer who spends his days “framing old illustrations, and … gilding wooden objects which he made himself.” When he feels especially alone and forgotten about, he takes the streetcar out to the suburban cemetery where his wife is buried. On returning home, he stops at the same café to sit at the same table and have a beer. His is a lonely, quiet life, haunted to a degree with regrets about how lonely and quiet it is.

And yet, in Romains’ unanimistic (I’ll get to that word in a moment) conception of the world, Godard has a double existence, so to speak, a kind of spirit life, of which, sadly, he’s not at all conscious.

For instance, there is a club, the Enfants du Velay, of which Godard is a member, in name mostly –

but it happened sometimes that his name would be spoken at one of the tables and that his image would hover for a moment upon the clouds of tobacco and the murmur of voices.

Or this. Godard was in occasional contact with his old co-workers from the railway. And sometimes –

he haunted occasionally the firesides of other pensioned railroad men or would suddenly appear before an old engineer standing on his platform and rushing full speed through space.

Or this. The memory of Godard lived on in the village he grew up in and occupied a kind of psychic/physical space alongside his parents as they sat in the evenings, dreaming –

The memory of Jacques filled the big kitchen, diffusing itself between floor and rafters with the smell of burning logs, brushing the table, reflecting itself in little mirrors made by a glass of wine or water, crouching in front of the sooty hearth and flying sparks, thrilled through and through by the cozy vibrations of the kitchen clock… All the village called Godard to mind. On such occasions he was present wherever anyone sat up at night… Thus it was that Godard, detached from himself, floated upon the world like a spray of seaweed torn from its rock.

* * *

The online Encyclopedia Britannica defines Unanimism as:

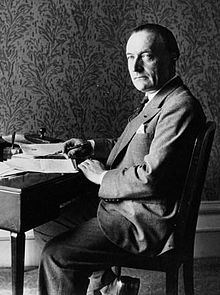

Romains (the pen name, actually, of Louis Farigoule) is also credited with formally founding the concept.

Image of Romains from http://rickrozoff.wordpress.com/

The Death of a Nobody is steeped in the idea of group consciousness, and there’s a simplistic, almost sentimental view of human relations at work informing the book. The tone throughout feels utopian and willfully naïve. (The Death of a Nobody [TDOAN from here on out] was just one part of a sprawling, multi-form project encompassing plays and poetry as well as novels, all gathered together under the absolutely un-ironic title of Men of Good Will. Part of the artist’s job, according to Romains and other followers of the Unanimistic way, was to come down from the ivory tower and reconnect to the commonweal; to be a part of the brotherhood of humanity.)

The plot, such as it is, is simple. After eight days of enduring a fever and a mysterious pain in his back, Godard suddenly dies.

Godard had time to think quite distinctly, ‘I’m dead. Where am I going? My God!’ He was aware that his soul was crumbling away again. Then he experienced a sensation entirely new. Something which was in him, which had served no purpose but to hold his life together, something contractive, elastic, formative, a sort of mainspring, suddenly let go, relaxed, expanded, and with a shiver of released vibrations, lost itself in space.

And presently he no longer knew that he was dead.

The porter of Godard’s building finds his body and sends a telegram to his parents to let them know. Then he lets the other tenants in the building know what’s happened to their neighbor. And once again, Godard is, in a manner of speaking, resurrected.

He [the porter, that is] informed the people on the first floor, a family on the second, who were kindly folk, then the neighbors on the fourth. They came out on the landing and entered the dead man’s room… Little by little the group reconstructed the soul of a retired railroad employee. The whole group possessed the soul of an old engineer, seated near his window, knocking out his pipe in the blue ash-tray, contemplating the colored calendar or the bunch of artificial roses thrust far down the neck of the opaque vase, or a frame he had finished gilding.

Each character in the book is activated by the energy or charge, if you will, of Godard’s death, even though he exerted no direct influence on their lives, at least while he was alive. He assumes prominence and even influence only once he’s dead. Yet there’s no cynicism or underhanded commentary implicit in this. Romains’ objective here is to illuminate this presumed collective consciousness, and he attempts it by examining the effect of the news of Godard’s death on people as it travels outward in ever-widening rings.

Still, it’s hard to determine what point Romains is trying to make with his overall theory of Unanimism. Making any kind of meaningful sense of it seems to require the application of flimsy generalizations in order to shore it up. Such as: people share information and experiences, and temporary allegiances can be formed from that. Or: like-minded people tend to find each other. Or: a group of people, even strangers can form a kind of unit, given a particular set of circumstances.

On the other hand, if a situation becomes dire, the worst sorts of self-protective behavior can emerge. Rather than band together, some people might retreat or even attack one another to get something they think is rightfully theirs. Or the sudden anonymity of being in a mob can unleash destructive behavior rather than philanthropic tendencies.

And so on. The upshot of the Unanimist point of view is that, in the case of TDOAN at least, it allows Romains the opportunity to assign a crowd of people attributes that one might under other circumstances assign to a single character. Which suggests to me that Unanimism’s ultimate value is purely aesthetic and, as such, extremely limited.

I’m also compelled to mention that the examination of crowds and crowd psychology has been dealt with in far greater depth elsewhere. Two obvious examples come to mind, one a work of non-fiction, one fiction. Elias Canetti’s Crowds and Power remains a definitive text, with its precise delineations between “the crowd” and “the pack,” and its ickily corporeal chapter titles: The Fear of Being Touched; The Discharge; The Entrails of Power.

And on a relatively more recent front, there’s the unforgettable mass wedding ceremony at Yankee stadium in the opening of Don DeLillo’s Mao II –

It knocks him back in awe, the loss of scale and intimacy, the way love and sex are multiplied out, the numbers and shaped crowd. This really scares him, a mass of people turned into a sculptured object. It is like a toy with thirteen thousand parts, just tootling along, an innocent and menacing thing…

The future belongs to crowds.

Image from http://entropymag.org/writers-their-pets/

Now this is a collective consciousness I definitely want in on.

But in his defense, Romains is sensitive to the subliminal workings and influences a given group is subject to. Wherever characters gather, be it in a hallway, a street, or a train, their being together, their shared humanness binds them psychically and emotionally, and Romains’ depiction of this group consciousness forming and performing can feel strangely familiar. For example, Godard’s father receives the news of his son’s death and begins the trip to Paris to arrange for his son’s burial. Here he is as he takes his seat on the horse-drawn carriage or diligence that will take him to the train station:

The others all stared at him for a minute, and he felt the forces from them intersect in him, like long needles in a piece of knitting. Little by little his right to be there increased: time united him to the others, as by a kind of glue that gradually hardens. He ventured to shift his seat and lean back. He was now really one of the group, steeped in it, and not merely imposed on it from without. They no longer stared at him; he had run the gantlet of all those eyes, and his soul was now like his companions’ souls.

I don’t know about you but this reminds me of settling in on a plane for a long flight. I might not feel any sort of connection with the people I’m surrounded by but what unfailingly goes through my mind is this – these might be the people I die with. And that, to some degree, generates a certain amount of tenderness toward them that I might not otherwise feel.

Another interesting aspect of Romains’ crowds is that there’s a deep and unique pleasure to be had in being part of one – in forming and expanding and inhabiting that unique consciousness, such as it is.

Here’s the crowd of mourners at Godard’s funeral as they move through the streets of Paris:

Thus the phrases left their lips and mingled with the chill air of the boulevard, without the transference of a single thought. But all the time, at the bottom of their hearts, in those regions of the soul that do not think, something was swelling and fermenting – a desire to overflow and join hands across the trivial chasms that part body from body, a growing promiscuity, a riot of tiny, blind intoxicated souls hustling and humming like a crowd at a wedding.

And once again our man Jacques Godard is in and of this crowd as well:

This general sense of well-being was far more beneficial to the dead man than tears had been. Since his heart had stopped beating he had never expanded thus. Every thread between him and the body had been severed, and, leaving his carnal part to rot in the coffin, he was free to multiply himself and take possession of a hundred living frames.

As the procession moves on, the crowd finds itself up against another crowd: striking laborers getting into a street fight with the police. But the power of death, or more specifically, the growing power of Jacques Godard, is enough to quell both sides. The cortege passes through and the laborers and cops, both humbled, stand at attention, the laborers removing their hats and wiping their brows, the cops saluting.

Then Godard is buried and all concerned go back to their lives, and in the process, the thing that Godard had become begins to dissipate. Romains stages a final spiritual flight with a stranger for Godard but, frankly, the book fizzles to a close.

The Death of a Nobody feels less like a Unanimist manifesto (say that ten times fast!) than it does a fictionalized depiction of what happens during the act of reading. In engaging with Romains’ text and conjuring up a version of the images that he puts on the page, a reader creates and possesses Godard’s “soul,” thereby assisting in bringing him to some kind of life. Godard “exists” as memory, as fantasy, as a kind of collective energy, because you, dear reader, make it and him happen. And as you read this, Godard, if only for a second, gets to live a little longer inside of you.

And so do I.