The Norwegian-based label Miasmah Recordings debuted its first physical release in 2006 with a compilation called Silva. Having little familiarity with any of the musicians on it at that time, I bought the cd on a whim, equal parts repulsed and intrigued by the silky and weirdly sinister cover art.

To this day, I remain a fan of the label and its founder, Erik K Skodvin, who busily produces music under his own name, as Svarte Greiner, and as half of the duo, Deaf Center.

In 2010, Miasmah released Schattenspieler (“Shadowplayer”) by Marcus Fjellström.

I snatched it up as soon as I could and became instantly smitten. While the music on it – crepuscular, haunted, prickly with vinyl hiss – lived up to its name, it also suggested to me the tiny vignettes and tableaux of shadowboxes. From there, my mind leapt to the Indo-Asian traditions of shadow puppetry, though the music itself was clearly sprung from the European avant-garde, more specifically, musique concrète. If there was a through-line between the two, it existed in my mind in the films of the Brothers Quay – not in their soundtracks so much as in the dream-turned-inside-out nature of their imagery. This was highly visual music, operating at an almost synaesthetic level.

A few tracks on Schattenspieler begin abruptly, almost in mid-note, giving testimony to their pre-recorded nature. Melodies are suspended in gently crackling clouds, shot through at times with anguished violin swells, keening flutes, or the occasional clap of a snare drum. Sounds throughout are detuned and distorted. Flutes turn to distant steam whistles, a siren becomes a horn, a horn stretches into a violin sound, a cymbal crash shatters in a cloud of dust. Loops are built and then torn open. Structures mutate. Fjellström has said in an interview that much of the music was played live, recorded, and then manipulated electronically. Some of it was sampled from old public domain films in his personal library.

I played the disc repeatedly, entranced by the singularity of the music, the single-minded vision of it. By the smoky, speculative movies it sent spooling through my head.

I tracked down Fjellström’s first two albums, Exercises in Estrangement from 2005 and Gebrauchmusik from 2006, both of which were starkly different from Schattenspieler in their explosive dynamics and the ways they openly displayed their post-classical, avant-garde influences. While I could appreciate the work, both discs left me a bit cold, though both had moments, glimmers of where Fjellström would take his music with Schattenspieler. And I wanted back into that world.

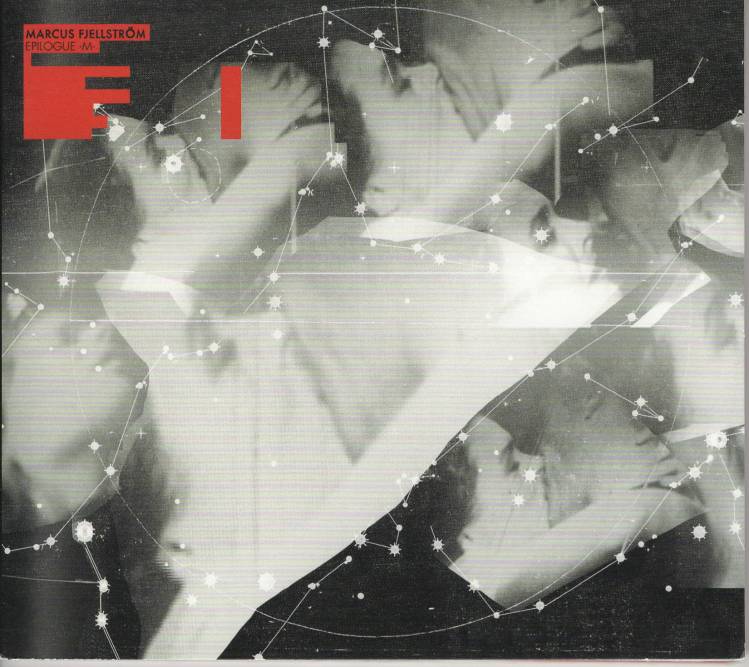

Then in 2013, the Epilogue-M– ep arrived from Aagoo, leaping out of the gate with “Dance Music 3,” a fractal plant clipping and continuation of the Dance pieces on Gebrauchmusik. Frantic, breathless, the music sounded like the marriage of a mechanical whistling bird and a wind-up glockenspiel. I imagined a perseverating number counter, tallying under her breath and spinning in ever-widening, erratic circles whenever I listened to it.

After that initial, spiraling blast-off, however, the tempo, set at a brisk 172 BPM, plunged. And where Schattenspieler had a dusty, dark quality, Epilogue-M- felt icy, crystalline. The same clicking, crepitating atmosphere held sway overall, but a frost had settled on everything. Notes and sounds glinted, appeared brittle, almost melting on contact from the heat of being heard. Percussive sounds predominated, bringing to my mind, especially on the close of the track “Puretos,” the ringing, resonating metallics of Harry Bertoia’s music. And there was a system at work it seemed, an interstellar theme in the constellation maps of the album’s artwork, overlayed on the image of a couple kissing. A fated, stars-aligned, smoldering romance, perhaps? But if so, why all the chilly, remote music?

I later discovered that Fjellström, since 2006 and the release of Gebrauchmusik, had also been exploring the world of film, taking on complete animation production duties for a handful of morbidly amusing, short films. While I won’t exactly recommend seeking out these early experiments, they can all be found on YouTube, under the Kafkagarden name. Something I do think worth mentioning, however, are his Odboy & Erordog films.

Looking like a fuzzed-out, black & white, mid-80s computer game, and inspired in part by childhood nightmares, the three-part saga of Odboy & Erordog (here, here, and here) is another complete Fjellström production. While the animation is still limited, the subject matter still grim, and the irony still heavy-handed, the filmic technique is more accomplished then in his earlier films, the synchrony of movement and music more sophisticated. It seems as if Fjellström decided to turn his efforts toward making the image and the story fit the music rather than using music to reflect the story and the image. Progressing from film to film within the series, there’s a marked improvement in technique and facility. And when the final story is told, Fjellström drops his ironic stance completely and manages to achieve a solid balance of music, image, story, and emotion. The final tale, in which Odboy and Erordog come to a parting of the ways, is unexpectedly heartbreaking.

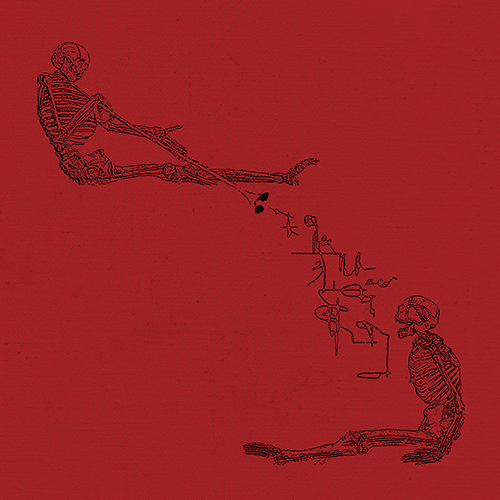

In November of 2016, I was happy to hear that Fjellström was coming out with another full-length album, Skelektikon.

Once again, I snapped it up as soon as I was able. And once again, I was happy to be back in that world. But things had changed. There was a new kind of clarity to the music on Skelektikon, not to suggest any sort of brightness in any way. While a track like “Modulus” had the trademark aged-vinyl haze in the background, other tracks like “Something Comes From Nothing” and “Aunchron” were almost chiaroscuro in comparison. The cobwebs and fog and frost had been swept away, and the music was being made to stand out in relief. There were songs on Skelektikon, as opposed to sound collages or speculative soundtracks. There was also an emotional gravitas, a deep, despairing, dirge-like sadness at the heart of the album, as if some vital energy had been drained away from the compositional process, a quality that further separated it from his earlier work. Fjellström had said in an interview that the album was completed during a time of heartbreak for him. The last minute of the closing track, “Boy With Wound,” sounds like something, or someone, dropping off into a void. We track their fall until the darkness swallows them completely. And then, nothing.

* * *

In September, I came across an article reporting that Marcus Fjellström had died.

I’ve looked around the internet since then for more information, but everything I’ve come up with is scant. What’s consistent in anything I’ve found, aside from the shock at the sudden death of such a talented, promising artist, is the feeling of loss over what could have been. Writing this post has been my way of processing some of those feelings as well. (And if you’ve read this far, thank you.)

Fjellström had recently finished a chamber opera, Boris Christ, for which he had composed the score and provided the elaborate visuals. Will it ever be performed in its intended entirety? Who can say?

This is also another full-length album, from 2011, Library Music, Vol. 1 that I never got around to picking up. But I imagine I will.

I know that there are individual tracks here and there that appear on compilation discs, and other videos scattered around YouTube. But I won’t steer you to them. It’s too much like scrambling to dig up every last scrap without considering that once you find that last scrap, it’s over. There’s nothing left to discover. It’s a second death, in a way. And I’d rather appreciate and share what’s still alive about his work.

Rest in peace, Marcus.